By Steven Huff

Stamford, New York, is a village in the lower elevations of the Catskill Mountains, near the Delaware River. One gets the sense that it hasn’t changed very much over many years, despite the presence of a few chain stores and ATMs. Small, comely, it would be a comfortable place to get snowed in. Part of the village is in the Town of Stamford, part in Harpersfield. I drove south on Route 10 from the New York State Thruway Exit 29. You can approach it from Route 23, but I found that scenic Route 10 is rewarding. A little north of Cobleskill is a stone marker, “Near this spot, Catherine Merckley, on October 18, 1780, fleeing on horseback from the Indians was shot and scalped by Seths Henry.” This followed by two and a half years the Battle of Cobleskill, May 30, 1778, in which Loyalists and Iroquois led by Mohawk leader Joseph Brandt attacked and destroyed much of Cobleskill.

The Town of Stamford, of which the village is part, was founded in 1792, the first settlers having arrived ten years before. In the War of 1812, little Stamford contributed more than twenty officers and around a hundred and twenty foot soldiers, which must have left farms and businesses short of strong-backed youth. But the war on the home front that year was with wolves encroaching on farmers’ stock, and a five dollar bounty was paid for each wolf shot.

The oldest Stamford house on the west side of the Delaware River was the birth place in 1823 of Edward Zane Carroll Judson, a.k.a. E. Z. C. Judson, a.k.a. Col. Judson, later famous for his dime novels written under his pen name, Ned Buntline. His great grandfather Samuel Judson was one of the town’s first settlers. Broad traveler, adventurer, luxury seeker, bloviator and con-artist though Ned was, the quiet bucolic Stamford would remain his hometown where he would shelter from his life’s storms.

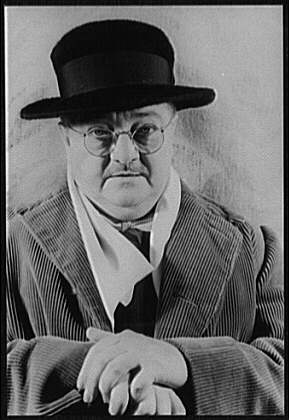

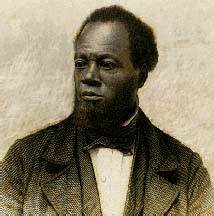

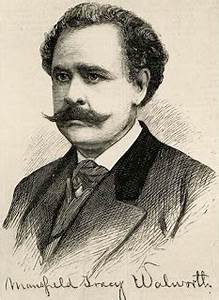

Ned Buntline (1823-1886 )

Ned Buntline was about as complicated and flamboyant as any author who ever lived. He campaigned for temperance, but alcohol was probably the only thing he was ever temperate about— and that only sometimes. In fact he was occasionally drunk when lecturing to temperance gatherings, so he knew whereof he preached. In addition to the above mentioned virtues, he was also a bigamist, bail jumper, and a natural-born showman. In his best years he was estimated to be the wealthiest author in America, money he earned from the sale of the dime novels that he cranked out, one after another, at least four-hundred of them, mostly adventure yarns.

Before he gained fame as a novelist he wrote stories for magazines, most notably the Knickerbocker, a respected literary journal, which is curious considering the hack quality of his later work. But Buntline also started and published several magazines. One of them, Ned Buntline’s Own, carried a regular feature about himself, from which many of the fables of his life gained currency, and thus are hard to corroborate.

Many biographers have tried to nail down his personality and found themselves in a thicket of contradictions. But all have agreed on his noted bonhomie. As T. M. Bradshaw has written, “Actual crimes, schemes, and lying manipulations aside, he was known as pleasant company, a genial, good-natured, friendly man,” also, “intelligent and creative but completely heedless of real consequences.”

Biographers have debated the old story that Buntline special-ordered the Colt company’s long-barreled .45 revolver, and gave it its name, the Buntline Special, as gifts to some of his western friends such as Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and others. However, the Colt company’s records do not support that any such order or purchase came from Buntline himself. It may be true. Or it may be just another Ned legend.

Off to Sea

When he was still a boy, his father moved the family from Stamford to Philadelphia so that he could study law. Ned, hating the cramped city, snuck aboard a fruit ship from the West Indies. He may have lied about his age to the captain who put him to work as a cabin boy, since he was only 11 years old. It was the beginning of a short career working on merchant ships. He may have lied about his age again when he joined the Navy in 1837, aged 14.

Most of his accounts of his heroic Navy years are probably yarns, but one bona fide adventure occurred aboard a small boat on route to the Brooklyn Navy Yard with a load of sand when it capsized after colliding with a ferry, and seventeen men went overboard into the icy water of the East River. Ned’s actions helping the men stay above water until rescue led to his appointment by President Van Buren to midshipman aboard the warship Boston.

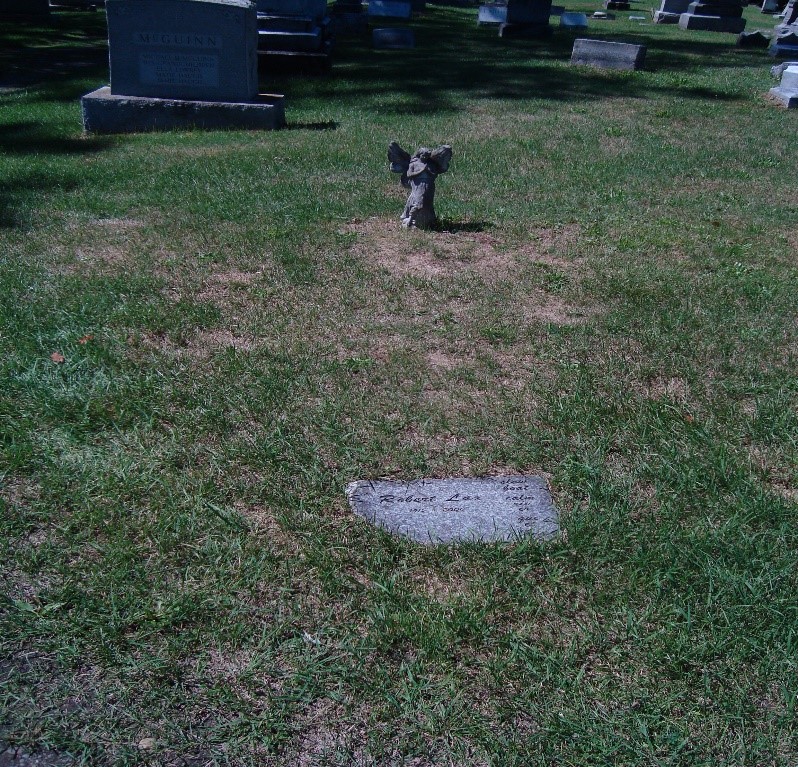

His name on his grave stone in Stamford Cemetery is Col. E. Z. C. Judson, a rank that he never held. As a midshipman in the Navy during the Seminoles Wars he saw little action. He claimed that in the Civil War he fought on with Gen. Sherman after Appomattox; in fact he was once jailed for desertion, often cited for drunkenness and insubordination, and dishonorably discharged in August 1864. While on furlough in Washington, he went to Mathew Brady’s studio, and sitting himself in the famous chair that Lincoln had been photographed in, he posed in a colonel’s coat—an act of impersonating an officer that could have landed him in the brig again.

He married at least six times, and by some accounts as many as nine. According to biographer Julia Bricklin, he did not bother to divorce several of the women before remarrying.

The Porterfield Incident

One incident in which he was shot and wounded and lynched—and survived—made news far beyond his own magazine. Not long after the death in childbirth of his first wife Severina in 1846, he was in Nashville writing for one of his magazines and became involved with Mary Porterfield, the teenage wife of Robert Porterfield, fireman and auctioneer’s assistant. Both Buntline and Mrs. Porterfield protested their innocence, but various people had seen them together. Robert Porterfield, deranged with jealousy, went looking for Buntline with a gun, and fired several shots at him; Ned returned fired and mortally wounded Porterfield with a bullet to his head, and then turned himself over to the law.

To be fair, it was the second time Porterfield had gone after Ned with a gun, who apparently had no interest in fighting with Mary’s husband. But the citizenry was outraged. At his arraignment, Porterfield’s brother, along with a mob, burst into the courtroom and fired a gun at Buntline, who ran from the court with a bullet wound to his chest and hid in a hotel across the street; but with the mob still in pursuit, he jumped from a third floor window and was dragged to jail, stunned and injured, by law officers. Later that night, in a case of old-time western justice, the mob broke into the jail, captured and hung Buntline from an awning post in the village square.

From there, accounts of the incident are murky. But apparently he had friends at the scene—or at least persons with cooler heads—who cut him down in time, or by other accounts the rope simply broke, and his pals whisked him away. The court cleared him of any blame in the death of Porterfield, and he recovered from the bullet wound. But he suffered a limp for the rest of his life from his leap from the hotel window.

Following the incident, Buntline wrote in the Knickerbocker, “Mr. Porterfield was a brave, good, but rash and hasty man; and deeply, deeply do I regret the necessity of his death. His wife is as innocent as an angel.”

The Dime Novels

His novels require from the reader more than the usual suspension of disbelief. But in the years following the Civil War, the United States had a fairly large standing army in the west engaged in the Indian Wars. Buntline knew that most of them were garrisoned for long periods of time with little to do; and so he gave them what he knew they’d love: sensational yarns mythologizing white American heroism in the west, such as Buckskin Sam the Scalp-Taker, and Norwood, Or, Life on the Prairie. To many of his eastern readers the west was a mystery, and so they had little cause to doubt him.

He is most identified with his western novels, although they counted only a few of his oeuvre. Far more are sea adventures, The King of the Sea: A Tale of the Fearless and Free , The Queen of the Sea, Or, Our Lady of the Ocean: A Tale of Love and Chivalry; hardscrabble and adventure, The Virgin of the Sun: A Historical Romance of the Last Revolution in Peru, The White Wizard: Or, the Great Prophet of the Seminoles. Ned was especially fond of hunting and fishing, and his characters were also lovers of the open wilds, on land or sea.

The Creation of Buffalo Bill

In 1868, on a trip to Nebraska, he met a young man named William F. Cody who had been working as a civilian scout for the US Army under Gen. Philip Sheridan. Buntline liked his flamboyant personality. He wrote a purportedly non-fiction book about him, and his supposed exploits among Indians, and gave him a name—Buffalo Bill. He didn’t invent the name, however—it was a common moniker in the west at that time—but he made it stick to Cody. Buffalo Bill, the King of the Border Men was serialized in the New York Weekly in December, 1869. When Cody read the book, most of the heroics was news to him. Buntline also made him out to be a temperance advocate like himself—which was another stretch of imagination, since Cody liked his tipple.

But Bill too had a flair for show business, and Buntline made him famous, organizing and promoting a traveling show for him, Scouts of the Prairie, beginning in Chicago in 1872. The entertainment consisted of western scouts on horseback, Indians—sometimes real, sometimes actors—and a rough, hurriedly written script for good old-fashioned western shootouts.

The show was a success, repeated many times over, moving around the eastern half of the country from one big top to another. It hit one snag in St. Louis when Buntline was arrested in his hotel for jumping bale on a charge of incitement to riot in the city twenty years before. But con artist that he was, he jumped bail again, this time with the treasurer of the Kansas Pacific Railway having to make good on the thousand dollar bond.

Buntline wasn’t one to let adversity spoil his day. When Buffalo Bill decided to split with Buntline and run his own show, eventually to be called Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, casting none other than Wild Bill Hickock to play Buntline’s part (after all, unlike Buntline, Hickock and Cody where handsome fellows), Buntline started a rival show, bringing real Comanches instead of actors, and two white scouts, Arizona Frank and Dashing Charlie. And, anyway, he made easier money on Bill with the western novels, Buffalo Bill’s Best Shot, Buffalo Bill’s Last Trail, Buffalo Bill’s Last Victory.

Certainly he helped to create the romantic and largely mythical images of the American west, so perpetuated by authors like Zane Grey, and traded on by Hollywood actors and directors such as Tom Mix, William S. Hart, John Wayne, John Ford, Howard Hawks, and multiple TV shows of the 1950s. He sure made his mark.

Gravity caught up with Edward Zane Carroll Judson, a.k.a. Ned Buntline, on July 16, 1886 when he died of congestive heart failure in his Stamford home. In the last months of his life he was confined to an “invalid chair,” tended to by his last wife Anna Fulton. But the mayhem was not over. At least two former wives went after his Civil War pension. And Anna was forced to sell their house to make good on his debts.

Finding the Grave of Ned Buntline

Follow Route 23 (Main Street) east out of the village. Turn right is on Tower Mountain Road where you will find two cemeteries directly across from each other. Stamford Cemetery is on the right. From the small parking lot inside the gate, follow the car path straight back for a couple hundred feet. When you see a stone for Grant, turn right; the tall brown spire is visible from there.

His name of the stone is Col. E Z.C. Judson 1823-1886, also here are Irene A. Judson, “d. 1881 in her 4th year”; E. Z. C. Judson, Jr. 1881-1894; and Mrs. Anna Judson [no date].

Sources

Bradshaw, T. M. Ned Buntline: So Much Larger Than Life. Np. 2019 (ebook).

Bricklin, Julia. “The Many Wives of Ned Buntline.” HistoryNet.com (web) 2021. (accessed 4/19/21).

Duerden, Tim, and Ray LaFever, Images of America: Delaware County. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2016 (print).

Monaghan, Jay. The Great Rascal: The Life and Adventures of Ned Buntline. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1952 (print).

Munsell, W. W. “The History of Delaware County: Town of Stamford,” Genealogy and Historical Site.

https://www.dcnyhistory.org/books/munstam.html n.d. (accessed 3/27/2021).