Canandaigua: Austin Steward

By Steven Huff

Note: The information in this blog post will be added to the already-existing Canandaigua post for authors Stanton Davis Kirkham and John Mosher Chapin at inourhomeground.wordpress.com.

The City of Canandaigua has a small-town, lakeside atmosphere, very attractive to tourists, although the lake’s shoreline itself is distressingly overdeveloped and has been for generations. Once a Seneca village, it was burned by Gen. John Sullivan during the Revolutionary War to punish the Iroquois Five Nations for aiding the British. It was resettled by European whites, and by the 1790s had a public school. Here, in 1873, at the Ontario County Courthouse, Susan B. Anthony was tried and convicted for the crime of voting in the 1872 presidential election in Rochester. As happens so often, the judge and jury were on the wrong side of history. It is also home to the New York Wine & Culinary Center, and Sonnenberg Gardens–both very much worth a trip.

Of other literary note, Canandaigua is the birthplace in 1823 of Philip Spencer, a mid-shipman who in 1842 was hung with two other sailors aboard the U.S.S. Somers and buried at sea for the crime of conspiracy to mutiny, but without a legal court marshal, which led to scandal. He was probably the model for Herman Melville’s Billy Budd. Spencer, son of John C. Spencer, President Tyler’s Secretary of War, was a noted rake and rogue. A Navy court exonerated the ship’s captain, reasoning that had the men been merely confined aboard ship, they could have been released by other disgruntled shipmen and then mutiny would have ensued. Public opinion in the US was outraged, but as everyone knows, outrage sputters out eventually. Melville had a relative aboard the ship, a cousin named Lieutenant Guert Gansevoort, and so the author was certainly familiar with the story.

Canandaigua was the birthplace in 1880 of Arthur Garfield Dove, known as America’s first abstract painter.

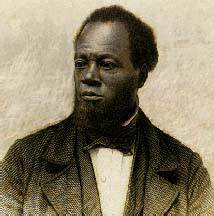

Austin Steward (1794-1869): From Slave to Freeman

He was born into slavery in Prince William County, Virginia, in the last decade of the eighteenth century, and migrated with his master to Central New York before the War of 1812. While there, Austin Steward escaped bondage. His memoir, Twenty-two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman, belongs among the great narratives of African-American experience in the ante-bellum years, such as The Narrative of Frederick Douglass, American Slave; and Twelve Years a Slave, by Solomon Northrop. It gives us a horrifying picture of slave life, but also a view of Upstate’s early settlements from the perspective of a man in bondage, and later of a free man who took his destiny into his own hands. He became a businessman in Rochester and an active abolitionist, helping slaves flee to Canada via the Underground Railroad.

Steward was put to work as a slave in the fields at age 7, and later made a household slave. His accounts of the lives of field slaves, of the thirty-nine lashes that one would receive with a heavy, lead-tipped whip allude to something even worse than senseless cruelty, but to an insane savagery, almost incomprehensible, in men who would have treated their horses and cattle gently. This brutality was more the norm than the exception, according to Steward, since lenient masters were despised by their neighbors. He relates details of an insurrection (years before Nat Turner) on the plantation of one such master that occurred when a patrol came to break up the slaves’ Easter festivities, in which the four members of the patrol and two of the slaves were killed.

The Journey North

His master, Capt. Helm, loved his leisure: poker, booze and race horses, and eventually gambled himself into penury. He sold his plantation and moved his household and slaves north to the recently settled Genesee Valley in New York State. Steward recalls that this was not good news to the slaves, who thought the Genesee to be beyond the pale of civilization, “where we should in all probability be destroyed by wild beasts, devoured by cannibals, or scalped by the Indians.”

He writes: “We traveled northward, through Maryland, Pennsylvania, and a portion of New York, to Sodus Bay, where we halted for some time. We made about twenty miles per day, camping out every night, and reached that place after a march of twenty days. Every morning the overseer called the roll, when every slave must answer to his or her name, felling to the ground with his cowhide any delinquent who failed to speak out in quick time.” Steward does not say how many slaves made the journey, but it must have been a considerable crowd since he does not mention any slaves left behind.

A New Country

There wasn’t much of a welcoming party at Sodus—only a single tavern. Capt. Helm bought a large tract of land on both sides of the bay and ordered his slaves to clear the woods. But hunger set in. The Virginians had no idea how to feed their multitude in the unfamiliar place. Slaves found wild animal bones in the woods and boiled them to make broth.

But things were different there in another significant way. The slaves sensed that they possessed a modicum of liberty in this new land. One day the overseer went into a cabin and found a slave named Williams whom he was determined to whip. But the slave was having none of it. “Instantly Williams sprang and caught him by the throat and held him writhing in his vise-like grasp, until he succeeded in getting possession of the cowhide, with which he gave the overseer such a flogging as slaves seldom get.” Shortly after, the monster quit his job and went back to Virginia.

Restless, Capt. Helm moved them all back down the valley to Bath, where he used the proceeds from the sale of his plantation–$40,000, or around $800,000 in today’s dollars–to found saw- and gristmills, which later proved unprofitable, and Helm began hiring out his slaves, including Steward.

The nation was readying for war with Great Britain. While hired out to a man in Lyons, Steward witnessed troops training for war with the British, a scene that became a carnival of drunken bedlam.

The Cost of Education

Steward found a spelling book, and began teaching himself to read. “But here Slavery showed its cloven foot in all its hideous deformity….I had been set to work in the sugar bush, and I took my spelling book with me. When a spare moment occurred, I sat down to study, and so absorbed was I in the attempt to blunder through my lesson, that I did not hear the Captain’s son-in-law coming until he was fairly upon me. He sprang forward, caught my poor old spelling book, and threw it into the fire, where it was burned to ashes; and then came my turn. He gave me first a severe flogging, and then swore if he ever caught me with another book, he would ‘whip every inch of skin off my back,’ &c.”

Steward said, “I found it just as hard to be beaten over the head with a piece of iron in New York as it was in Virginia.”

When Helm fell into financial trouble again he began selling his slaves, while others simply walked away. Steward bolted for freedom with the help of members of the New York Manumission Society, who told him that by virtue of hiring Steward out, Helm had forfeited legal ownership of him in New York—a technicality in the state’s 1799 Gradual Emancipation Statute. Dennis Comstock, of the Society, gave him money to help him get settled. Steward wrote, “the first thing I did after receiving it I went to Canandaigua where I found a book-store kept by a man named J.D. Bemis, and of him I purchased some school books.” Bemis was a noted supporter of progressive causes. There is a Bemis Street in Canandaigua.

Helm made one last grand effort to restore his wealth by attempting to kidnap his former slaves en mass and transport them back to Virginia to be sold. He threw a big party in Palmyra and invited them all; then, late at night, he closed in with a group of men to capture them. But it ended in a bloody battle, with many injured, including Steward’s father who succumbed later to his wounds, and Helm and his confederates went away empty handed. Steward himself had sensed trouble and had stayed away.

A Man of Stature and Eloquence

In 1816, Steward started a business in Rochester, on what is now West Main Street, selling produce and meat. He prospered, despite some local resistance from whites, and soon became a property owner in Brighton and Canandaigua.

The State of New York ended slavery in 1827, one of the last northern states to do so (although not until 1840 did a census find no slaves in New York). Steward, now married, and active in the Underground Railroad, celebrated the occasion with a speech in Rochester’s Johnson Square, exhorting former slaves to look forward to the hard work ahead of free people: “Let not the rising sun behold you sleeping or indolently lying upon your beds. Rise ever with the morning light; and, till sun-set, give not an hour to idleness. Say not human nature cannot endure it. It can—it almost requires it….Be watchful and diligent and let your mind be fruitful in devises for the honest advancement of your worldly interest. So shall you continually rise in respectability, in rank and standing in this so late and so long the land of your captivity.” It was an eloquent, memorable speech, a forerunner in some respects of the great orations that followed in Rochester by Frederick Douglass and William H. Seward, and the “First of August” celebrations, beginning in 1834, marking the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies.

Later he was elected vice president of the first meeting of the National Negro Convention Movement, held in Philadelphia in 1831.

That same year, he moved to Canada to join the Wilberforce Colony in London, Ontario, which had been founded for African Americans escaping slavery and agents who crossed into northern states looking for runaways. But he found the leadership of that colony corrupt, and in 1837 he moved back to Rochester. But he had spent all his wealth on the colony, and upon his return had to borrow funds to rebuild his business and reestablish a home. His autobiography, Twenty-two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman was published by William Alling in Rochester in 1857. He died in the winter of 1869 from typhoid fever.

Finding the Grave

Take Exit 44 from the New York State Thruway, and head directly south on Route 332. As you come into Canandaigua, it becomes South Main Street. A bit less than 9 miles from the toll booths you will find West Avenue, where you will turn right. If you come to Canandaigua on Routes 5 and 20, turn north on South Main Street, and in a few blocks you will find West Avenue. Turn left. Shortly after your turn, you will see the West Avenue Cemetery on the right, and you will find the front entrance where the hedge breaks.

Walk or drive in about 50 feet to an intersecting path, and turn to the right. The white granite spire for the Steward family, with footstones for him, his wife Patience, and several of their children are a about 25 feet ahead on the left.

Sources:

Austin Steward, Twenty-Two Years a Slave and Forty Years a Freeman (1856), The Project Gutenberg EBook, 2004; dann j. Broyld, “Rochester’s Black Pioneers: Austin Steward,” Rochester History, a Publication of Rochester and Monroe County Library, Christine L.Ridarsky, editor, Vol 72, No. 2, Fall, 2010; Preston E. Pierce, “Liberian Dreams: West African Nightmare: The Life of Henry W. Johnson,” Part 1, Rochester History, Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck, editor, Vol. LXVI, No. 4, Fall 2004; David Lewis, “Steward, Austin,” web, BlackPast.org., (accessed 1/9/19); Shirley Yee, “The National Negro Convention Movement,” BlackPast.org (accessed 1/28/19).

That’s quite a story. Thanks for this.

LikeLike