By Steven Huff

Newark, New York

Newark New York is a village in the Town of Arcadia on the Erie Canal, about half-way between Rochester and Syracuse. An area on its east side was once known as Lockville, where a cluster of three canal locks raised westbound boats entering Newark. The locks have been preserved for an historical park. Like most villages on the canal, it owes its early prosperity to Erie traffic. The presence of even one lock was good for local business, general stores and taverns particularly, simply because boats were delayed there and canallers availed themselves of whatever was at hand.

Famous dancer and choreographer Sybil Shearer (1912-2005), born in Toronto, grew up here. Journalist Harriet Van Horne (1920-1998) graduated from Newark High School. Songwriter, singer and animator Peter Hannan is from Newark. And, although few in Newark remember him personally now, there was author Charles Reginald Jackson.

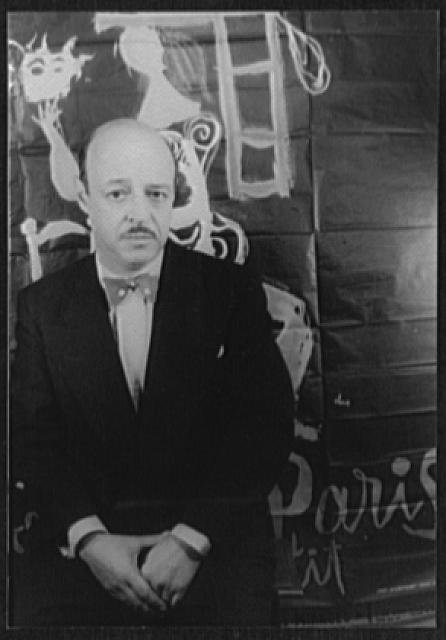

Charles R. Jackson (1903-1968) and His Lost Weekends

He was born in New Jersey in 1903, but grew up in Newark, New York, where his family lived in a small house on Prospect Street. Charles Jackson was kid addicted to books, who spent his weekend afternoons in the village library instead of on the ball field. In fact, that is where he was on November 12, 1916, when a call came for him to come directly home. His older sister Thelma, 16, and four-year-old brother Richard had been riding in a car that was hit by a passenger train at a nearby railroad crossing. Both were killed. Besides paralyzing the family, the tragedy traumatized the entire community.

At the funeral, the two siblings were laid out together in one casket, Thelma on her side as if napping, with Richard’s head on her arm and holding her hand. Not long after, the father, Fred, who had been working in Manhattan, wrote to say that he wouldn’t be coming home again. And thereafter, Charles grew very close to his mother, although their relationship was contentious.

The youths of many writers seem grounded in tragedy. Among Upstate authors, John Gardner was involved in a farming accident that killed his younger brother Gilbert; Adelaide Crapsey was devasted by her father being defrocked from the priesthood by the Episcopal Diocese of Rochester; Mark Twain’s brother died in a river boat fire. How much those traumas fired their creative drive is a matter for speculation, more things than can be dreamt of in my philosophy.

Charles Jackson—short and slight of build— was a closeted bisexual, which in those times was a scandalous complication, and may have been a driving force behind his later alcoholism. But who knows?—a boozer is a boozer, and whatever happens, he will find the bottle. He enrolled in Syracuse University in 1921, but left after a minor dustup over a brief relationship with another fraternity member. Four years later in 1925, he left Newark on a train for Chicago, and for years worked in bookstores and as a newspaper editor there and in New York City.

But in 1928 he began coughing up blood, and by 1929, living in Newark again, he went to Rochester General Hospital where collapse of his right lung was induced as a treatment for tuberculosis. Since antibiotics for the disease did not arrive until 1946, this was the only practical medical intervention, allowing tuberculous damage to heal. Finally, he and his brother Fred, who also suffered from the disease, went to a renowned sanitorium in Switzerland for treatment, which included rest and clean air, and sleeping in frigid temperatures. The bill was paid by Bronson Winthrop, a wealthy lawyer that Charles had befriended a few years before.

Unlike Rochester poet Adelaide Crapsey (See Rochester at Mount Hope Part 1), Jackson regained his health after his bout with tuberculosis.

The Lost Weekend

Jackson was a hard-working writer. While still in his teens he was local editor of the Newark Courier-Gazette, writing much of what passed for news in the small town. His first novel, The Lost Weekend— the story of five days and nights in the life of an alcoholic writer on a binge, which years later he admitted was largely autobiographical—made him famous, and while none of his other novels quite came up to it in critical acclaim or in sales, he remained a highly respected writer and a well-paid lecturer. It was translated into fourteen languages and, according to Jackson biographer Blake Bailey, aroused the jealousy of British poet and novelist Malcom Lowry who was hard at work on his own “alcoholic masterpiece,” Under the Volcano.

Focusing on a writer’s dipsomania—the romantic “tortured soul” notion that many readers have—is often a diversion from what truly matters about the works. But, as with Frederick Exley (Watertown), it is inescapable with Jackson. Lost Weekend was one of the big publishing events of 1944. Philip Wylie, in a review in The New York Times, said, “Charles Jackson has made the most compelling gift to the literature of addiction since De Quincey….[He] makes plain the psychic states which give rise to the morbid eloquence of Poe, on one hand, and to such phenomena, on the other, as the late F. Scott Fitzgerald’s identification of glamor with literal intoxication.” The book was destined for classic status.

Hollywood, Wilder and Brackett

Billy Wilder made it into a 1945 movie, which won the Oscar for Best Picture, Best Actor for Ray Milland, and a Best Adapted Screenplay for Wilder and Charles Brackett. But novelists are rarely happy with their film treatments. (Hemingway didn’t like any of his movies.) And Jackson, while initially thrilled with the script, wrangled with the Wilder-Brackett team when they tacked on an upbeat ending that they knew would be more palatable to the public and less apt to rile the Hays motion picture censors. He felt cheated, and became a nagging thorn in Brackett’s side, who wrote in his diary, January 2, 1945, “Charles Jackson’s letter arrived (a five-page agony of hatred of the final sequence). It sounded so repetitious it was like a loop….” The strife went on for months, Brackett calling Jackson “Birdbrain” in a telegram.

A few days later, a phone call from Jackson got Brackett out of the bathtub. Peevishly, he wrapped a towel around himself and went to answer it. “I said, ‘I don’t want to hear your voice. I don’t want to hear your name. I am just Goddamned bored!’ With that I hung up.”

Jackson was a devoted husband to his wife Rhoda and a doting father to his daughters. For long stretches of time he remained sober, even traveling as a national spokesman for Alcoholics Anonymous. It is worth listening to one of his talks, “Charles R. Jackson—Alcoholics Anonymous Speech (1959),” which is available on YouTube. He mentions there that he did not actually begin drinking to excess until age 26, unlike most big drinkers he had known who were more precocious boozers. Although, even while traveling for AA, he had trouble staying out of the sauce. Near the end of his life, he deserted his family as had his father before him. He died in 1968 from an overdose of barbiturates at Saint Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan (where Dylan Thomas had died from inebriation fifteen years before). Jackson was 65.

And yet, all considered, his life was a triumph, not only over tragedy, tuberculosis, and stretches of time lost to alcohol, but over the self-doubt that plagues every writer. Inside of this small man was a core of strength and genius.

His Books

His books that followed Lost Weekend were, The Fall of Valor (1946); The Outer Edges (1948); The Sunnier Side: Twelve Arcadian Tales (1950), Earthly Creatures (1953), and A Second-Hand Life (1967).

Finding the Grave

No freeway goes to Newark, but trusty Route 31 runs through it, the road that more than any other runs parallel to the Erie Canal in Central and Western New York. Coming from the east on the Thruway, get off at Exit 42 for Geneva and Lyons; take 14 north several miles to Lyons and turn west on Route 31. From the west, take Exit 41 for Palmyra and travel east on 31. Or set your GPS for Vienna Street, Newark, NY, 14513.

In the center of the village, turn south on Main Street, then left (east) on East Maple Avenue, which, in about a mile, will intersect with Vienna Street, where you will turn right. You will find the main gate of East Newark Cemetery a short distance on the left. The main road into the cemetery is called Pine Street. Take this road, passing a wooden shed on the right. You will see Aspen Street on the left. But Aspen is actually a loop. Go to the second intersection with Aspen. The Jackson family plot is on the neast corner. Charles Jackson is nearest to the corner. Next to him is the grave of Thelma and Richard. Their mother Sarah and brother Fred are nearby.

Sources:

Charles Jackson, The Lost Weekend, Introduction by Blake Bailey, New York: Vintage Reprint Edition, 2013; The Lost Weekend, Dir. Billy Wilder, Principle performers, Ray Milland, Jane Wyman, Paramount 1945; Charles Brackett, “It’s the Pictures that Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, Edited by Anthony Slide, Foreword by Jim Moore, New York: Columbia University Press, 2015; Blake Bailey, Farther and Wilder: The Lost Weekends and Literary Dreams of Charles Jackson, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013; Philip Wylie, “Wingding,” New York Times Book Review, January 30, 1944; Charles R. Jackson—Alcoholics Anonymous Speech (1959) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoiP5xsJzvs (accessed 12/27/18); John R. Groves, “Where is Lockville?” Wayne County Life, 31 Oct., 2008, web., (accessed 1/5/19).

Fascinating, Steve.♥️♥️

Judy 🐓

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always a treat to read. Thanks Steve….from an old classmate.

LikeLike