Buffalo, Forest Lawn, Part 3: Shirley Chisholm and Edward Streeter

Buffalo’s Forest Lawn Cemetery was founded by lawyer and businessman Charles Ezra Clark in 1849, the year that he was elected to congress as a Whig, although he himself is buried in Brookside Cemetery in Watertown. To the list of famous interments in “Buffalo, Forest Lawn” Parts 1 and 2, I would add Dr. Frederick Cook (1865-1940), reputed discoverer of the North Pole; William Fargo (1818-1881), cofounder of the American Express Company and Wells Fargo; and E. R. Thomas (1850-1936), early car manufacturer whose 4-cilander Thomas Flyer in 1908 won the only around-the-world race ever held.

And we mustn’t forget the contributions of Buffalo dentist Alfred P. Southwick (1826-1898), also buried in Forest Lawn. He was the inventor of the electric chair, first used at Auburn Prison on August 6, 1890. There had been a number of botched hangings around the country in recent years, and authorities wanted a humane alternative. Sound familiar? The lucky Number One, William Kemmler, a convicted murderer also from Buffalo, was dispatched to the stars on the above date, despite his lawyers’ efforts to stop it on the grounds of cruel and unusual punishment. The lights would dim all over the City of Auburn whenever they threw that switch. Anarchist Leon Czolgocz would be executed in that chair in 1901 for the assassination of President McKinley in Buffalo. Prior to Kemmler’s execution, the contraption was tested out on stray dogs by the Humane Society.

Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005) Unbought and Unbossed

She was a fighter in the best sense of the word. A teacher and political organizer in her native Brooklyn, Shirley Chisholm served in the New York State Assembly, starting in 1965, where she quickly gained a reputation for being a scrapper, for not playing political poker with the big powers, and for being unpredictable. In 1968 she became the first black woman elected to the U.S. Congress where she served until 1983, and where she fought for refugees, Native American land rights, legal services for the poor and the marginalized, and for special education, and was the first woman to seek the Democratic Party nomination for president. (Margaret Chase Smith, Republican, was the first to run for a major party’s presidential nod in 1964.) Her campaign slogan was “Unbought and Unbossed.” The mention of her name was almost always in the context of feminism, peace and justice, and sanity.

She did what she thought was right, and damn the torpedoes. She visited Gov. George Wallace in the hospital after he was shot in Maryland while running for president, bring stinging criticism down on her head; after all, he was the one who stood in the schoolhouse door to resist desegregation of schools in Alabama. He later helped her win the votes she needed to win minimum wage for black women workers. Being unpredictable pays dividends to the honest. According to his daughter, Chisholm’s kindness touched Wallace deeply, and began to make him realize that his segregationist ideas were wrong.

But few think of her as an author. Yet her best known book, her autobiography Unbought and Unbossed (1970), was republished a few years ago in a 40th Anniversary Edition. It is a strong book, and an eye-opener. She was born in 1924 in New York City to immigrant parents from Barbados. They may have hoped that the United States would be their promised land. But when her father was out of work, she was sent along with her two sisters to their family farm in Barbados where they were raised by their grandmother until their parents could get on their feet. She credited the British school system on the island for the quality of education that gave her the advantage to take leadership roles in her community and, eventually, in the US Congress. And for her ease at writing.

After her retirement from Congress, she moved to the Buffalo suburb of Williamsville. She died on New Years Day 2005 in Florida where she had later moved. But in death she returned to her adopted community of Buffalo.

Finding the Grave

Shirley Chisholm is in the Birchwood Mausoleum. From the main gate, follow the yellow-, blue- and white-lined path, which turns to the right before the bridge over the Scajaquada Creek; continue to follow past Mirror Lake and the grand field of mausoleums to a second bridge over the creek, after which follow the yellow route up the hill. Birchwood Mausoleum is No. 6 on the Overview map. She is in the Center Lane, Wall 32, Row 158, Tier F, which may or may not be helpful. Walk in the front door. Her crypt is about 12 feet off the floor on the left side, which she shares with her second husband Arthur Hardwick. The epitaph, “Unbought and Unbossed” is slightly legible.

Sources: Jacqueline Trescott, “Shirley Chisholm in Her Season of Transition,” The Washington Post, June 6. 1982, web (accessed 11/10/18); Vanessa Williams, “’Unbought and Unbossed’: Shirley Chisholm’s Feminist Mantra Is Still Relevant 50 Years Later,” The Washington Post, January 26, 2018; Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed, Take Root Media Edition, 2010, Washington, DC, copyright © 1970 by Shirley Chisholm.

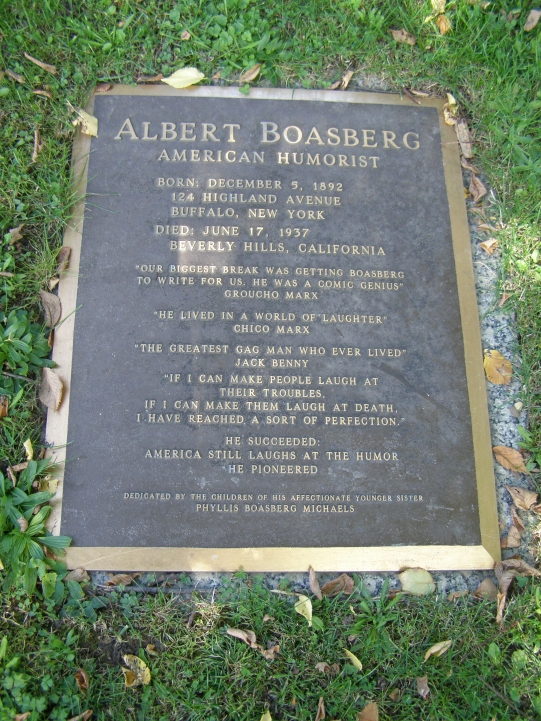

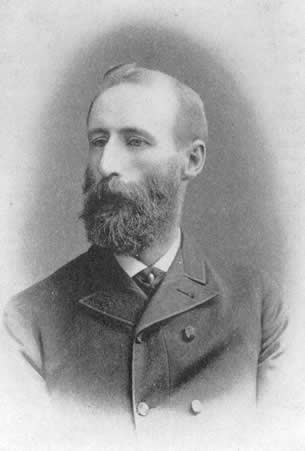

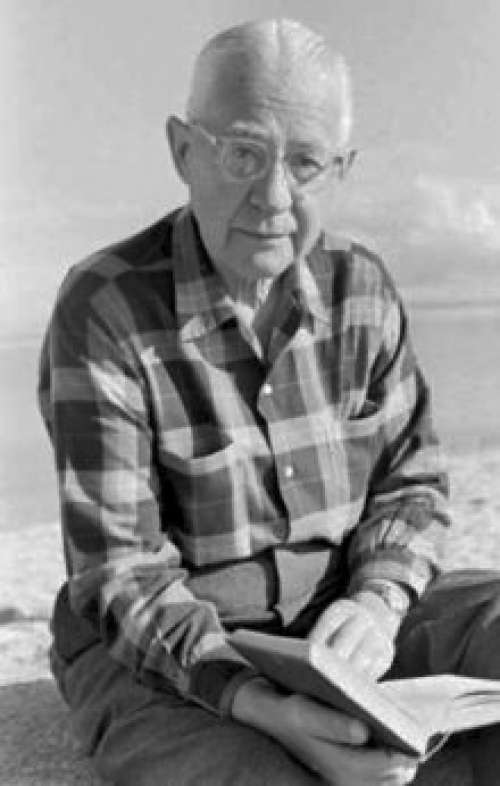

Edward Streeter (1891-1976) Novelist, Satirist…and Banker

It is hard to think of another successful American writer who was also a banker. I’m talking about Edward Streeter, twenty-five years as vice-president of the Bank of New York. Before that he did eight years at Bankers Trust. Well, Wallace Stevens comes close: he was vice-president of a major insurance company. I’ve known a few writers who had a lot of money, but a banker? It does not seem that one individual would be able to survive with those very antithetic ambitions. He must have been hilarious to work with. When someone remarked to Robert Graves that there’s no money in poetry, he answered, “There’s no poetry in money, either,” and he was right. I once tried to get a job as an insurance agent, but when they found out that I didn’t have any insurance myself they turned me down, and rudely. I can imagine what they would have said if I’d told them I was a poet. But let me set my doubts aside for a moment.

Edward Streeter was born in Buffalo in 1891, attended Harvard University, and became a World War I correspondent for the Buffalo Express, which later became The Buffalo Courier Express. The Express, by the way, was the paper Mark Twain wrote for when he lived in Buffalo, but had gone on to fame before Streeter was born. During World War I, Streeter started a regular newspaper column titled “Dere Mabel,” [sic] which were the endearing letters from a fictitious soldier named Bill with spelling problems, writing to his true love. The column was very popular during the war, and after the conflict ended they were compiled in a book, Dere Mabel, and it was a bestseller. It hatched into a series, including That’s Me All Over Mabel; and Same Old Bill, Eh Mabel? Americans love to feel sentimental about our wars.

Then Streeter went into banking and joined the New York City vortex. But he didn’t disappear. He continued to write articles and short stories for the slick mags. And in 1938 he published a novel, Daily Except Sundays, a satire of New York City commuters. Do Americans want to bust a gut laughing about struggling to get to work? They used to, apparently. They take it too seriously now. Maybe someone should update Streeter’s Daily to include twenty-mile backups, road rage, and getting dragged off of airplanes by security.

Ah, the Bride!

He hit it bigger in 1949 with the novel Father of the Bride, a satire of a man’s paroxysms of love and anxiety as his daughter gets ready to march down the aisle. This one elevated him to the higher offices of fame because, not only because it was a bestseller, but the following year it became a movie with Spencer Tracy, Joan Bennett, and Elizabeth Taylor as the bride. Now he was on a roll. Next came Mr. Hobbs’ Vacation (1954), which also became a movie in 1962 with James Stewart and Maureen O’Hara. His novel, Merry Christmas, Mr. Baxter (1956), was adapted for NBC’s The Alcoa Hour, starring Dennis King, Patricia Benoit and Margaret Hamilton. He was retired now, and he could spend all the time he wanted writing books, and he produced four more, though they did not pack the wallop that his earlier books did. Father of the Bride was also a TV series from 1961-1962.

His novels are known for dry wit, and insight into the modern human condition. Streeter’s “genial thesis,” said the New York Times review of the film version of Mr. Hobbs’ Vacation, is that “the family unit is perhaps the most anomalous and irritating social arrangement ever devised by so-called civilized man.” The family unit survives Hobbs’ holiday, said the reviewer, but “Mr. Streeter has still got in some nice, sharp, accurate digs.”

Edward Streeter holds a deserved place in American pop culture. His books may not be classics, but he is not forgotten—not at all. If you want to read them, they’re available online. Or a librarian will go to the basement and get a copy for you from the stacks. They’re down there somewhere. Father of the Bride (1950) is now considered a classic movie. The 1991 remake does not come close to it. If you see Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show you’ll see a short clip of the original in one of the movie theater scenes. But even those few seconds have enough gravitas to send you to the library for the DVD. It is, after all, a good story.

Finding the Grave

Streeter made his fortune in New York City, where he died in 1976; his funeral was held at St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church on East 56th Street. But for his burial, it was time to come home to Buffalo. He is buried in Section 9 at Forest Lawn Cemetery, and he is easy to find. From the entrance, follow the Yellow, Blue and White Path. After you pass the Red Jacket monument on your right you will pass Sections 11 and 8 on your left. The next section on your left is 9. There is a triangular roundabout there with a spreading fern tree. Prominent on the nearest point of Section 9, facing the roundabout and just to the left of a Rose of Sharon tree is a monument to James D. Warren (who in the nineteenth century was editor and proprietor of The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser and a Republican stalwart). Around it are twenty-three smaller markers for individual members of his family, and Edward Streeter is one of them, three markers to the right of the monument. Streeter was married to Charlotte Warren Streeter, of James D.’s family, and they kindly made room for him in the family plot. His stone has not weathered well these forty–plus years, so you must look closely to read his name.

Sources: “Edward Streeter, Humorist, Dies at 84,” New York Times Obituary, April 2, 1976; “Edward Streeter: Accomplished Novelist, Journalist…and Banker,” www.forest-lawn.com/blog/2017/03/30/edward-streeter ;”Edward Streeter,” Revolvy.com, web; Bosley Crowther, “Screen: ‘Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation’: Edward Streeter Book Twists Family Life,” New York Times, June 16, 1962. Obituary, Mrs. Charlotte Warren Streeter, New York Times, January 3, 1966.